The Story of Bhagat Singh's Prison Notebook....by Kalpana Pandey

New Delhi: On the occasion of the martyrdom day of Bhagat Singh and his comrades Sukhdev and Rajguru, let us briefly explore Bhagat Singh’s jail diary.This diary, similar in size to a school notebook, was given to Bhagat Singh by jail authorities on September 12, 1929, with an inscription stating “404 pages for Bhagat Singh.”

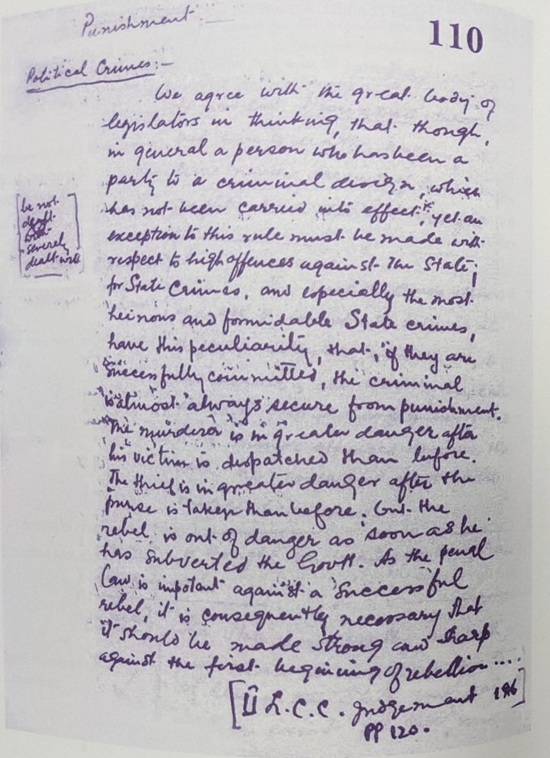

During his imprisonment, he made notes in this diary based on 43 books written by 108 different authors, including Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Lenin. He took extensive notes on history, philosophy, and economics.

Bhagat Singh’s focus was not only on the struggle against colonialism but also on issues related to social development. He was particularly inclined toward reading Western thinkers.

Moving beyond nationalist narrow-mindedness, he advocated for resolving issues through modern global perspectives. This global vision was something only a few leaders of his time, such as Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, possessed.

In 1968, Indian historian G. Deval had the opportunity to see the original copy of Bhagat Singh’s jail diary with Bhagat Singh’s brother, Kulbir Singh. Based on his notes, Deval wrote an article about Bhagat Singh in the periodical People’s Path, where he mentioned a 200-page diary.

In his article, G. Deval noted that Bhagat Singh had made annotations on topics like capitalism, socialism, the origin of the state, Marxism, communism, religion, philosophy, and the history of revolutions.He also suggested that the diary should be published, but this did not materialize.

In 1977, Russian scholar L.V. Mitrokhov came across information about this diary. After gathering details from Kulbir Singh, he wrote an article that was later included as a chapter in his book Lenin and India in 1981. In 1990, Lenin and India was translated into Hindi and published by Pragati Prakashan, Moscow, under the title Lenin Aur Bharat.

On the other hand, in 1981, G.B. Kumar Hooja, then Vice-Chancellor of Gurukul Kangri, visited Gurukul Indraprastha near Tughlaqabad, Delhi. The administrator, Shaktiveśh, showed him some historical documents stored in the basement of the gurukul. G.B. Kumar Hooja borrowed a copy of this notebook for a few days, but he was unable to return it as Shaktiveśh was murdered shortly after.

In 1989, on the occasion of the martyrdom day of March 23, some meetings of the Hindustani Manch were held, attended by G.B. Kumar Hooja. There, he shared information about this diary.

Impressed by its significance, Hindustani Manch announced the decision to publish it. The responsibility was given to Bhupendra Hooja, editor of the Indian Book Chronicle (Jaipur), with support from Hindustani Manch General Secretary Sardar Oberoi, Prof. R.P. Bhatnagar, and Dr. R.C. Bharatiya.

However, it was later claimed that financial difficulties prevented its publication. This explanation seems unconvincing, as it is unlikely that the educated middle-class individuals mentioned above could not afford to print a few copies at a time when costs were relatively low. It is more plausible that they either failed to recognize its importance or simply lacked interest.

Around the same time, Dr. Prakash Chaturvedi obtained a typewritten photocopy from the Moscow archives and showed it to Dr. R.C. Bharatiya. The Moscow copy was found to be identical, word for word, with the handwritten copy retrieved from the basement of Gurukul Indraprastha.

A few months later, in 1991, Bhupendra Hooja began publishing excerpts from this notebook in the Indian Book Chronicle. This was the first time Shaheed Bhagat Singh’s jail notebook reached the readers.

Alongside this, Prof. Chamanlal informed Hooja that he had seen a similar copy in the Nehru Memorial Museum, Delhi.

In 1994, the jail notebook was finally published in book form by Indian Book Chronicle, with a foreword written by Bhupendra Hooja and G.B. Hooja. However, neither of them was aware that the original copy of the book was with Bhagat Singh’s brother, Kulbir Singh.They were also unaware of G. Deval’s article (1968) and Mitrokhin’s book (1981).

Furthermore, Dr. Jagmohan Singh, son of Bhagat Singh’s sister Bibi Amar Kaur, never mentioned this jail notebook. Similarly, Virendra Sandhu, daughter of Bhagat Singh’s brother Kultar Singh, wrote two books on Bhagat Singh, but she too did not reference this diary. This suggests that Bhagat Singh’s family members were either unaware of the notebook’s existence or had no interest in it. Although Kulbir Singh possessed the diary, he never attempted to share it with historians, publish it as a book, or release it in newspapers. His financial condition was not so dire that he could not afford to publish it himself.

It is unfortunate that Indian historians neglected this significant historical document, and it was first published by a Russian author.

The Congress party, which remained in power for the longest time, showed no curiosity about Bhagat Singh’s intellectual and ideological contributions to the freedom movement. Their ideological differences with him might have been the reason why they never focused on researching Bhagat Singh’s thoughts and actions.

After establishing the Bhagat Singh Research Committee, Bhagat Singh's nephew, Dr. Jagmohan Singh, and Professor Chamanlal from JNU's Indian Languages Center compiled and published the writings of Bhagat Singh and his comrades for the first time in 1986 under the title Bhagat Singh Aur Unke Sathiyon Ke Dastavej. Even in that publication, there was no mention of the jail notebook. It was only in the second edition, published in 1991, that it was referenced. Currently, the third edition of this book is available, in which the two scholars have undertaken the invaluable task of adding several rare pieces of information and presenting them to the readers.

The notes taken by Bhagat Singh in this notebook clearly reflect his perspective. His restless yearning for freedom led him to transcribe the thoughts of Byron, Whitman, and Wordsworth on liberty. He read Ibsen’s plays, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s renowned novel Crime and Punishment, and Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. He also read the works of Charles Dickens, Maxim Gorky, J.S. Mill, Vera Figner, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Charles Mackay, George de Hesse, Oscar Wilde, and Sinclair.

In July 1930, during his imprisonment, he read Lenin’s The Collapse of the Second International and "Left-Wing" Communism: An Infantile Disorder, Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid, and Karl Marx’s The Civil War in France. He took notes on episodes from the lives of Russian revolutionaries Vera Figner and Morozov. His notebook even contained verses from Omar Khayyam. To obtain more books, he persistently wrote letters to Jaidev Gupta, Bhau Kulbir Singh, and others, requesting them to send him reading material.

On page 21 of his notebook, he wrote the quote by American socialist Eugene V. Debs:

“Wherever the lower class exists, I am there; wherever criminal elements are, I am there; if anyone is imprisoned, I am not free.”

He also made notes on the freedom struggles of Rousseau, Thomas Jefferson, and Patrick Henry, as well as on the inalienable rights of man. Additionally, he recorded the famous quote by writer Mark Twain:

“We have been taught how horrifying the beheading of people is. But we have not been taught that the death wrought by the lifelong imposition of poverty and tyranny upon all people is even more dreadful.”

To understand capitalism, Bhagat Singh made numerous calculations in this notebook. At that time, he recorded the inequality in Britain – one-ninth of the population controlled half of the production, while only one-seventh (14%) of the output was distributed among two-thirds (66.67%) of the people. In America, the wealthiest 1% held $67 billion in assets, whereas 70% of the population possessed only 4% of the assets.

He also quoted a statement by Rabindranath Tagore in which the Japanese people's lust for money was described as "a terrifying threat to human society." Furthermore, he referenced bourgeois capitalism by drawing from Maurice Hillquit's Marx to Lenin. Being an atheist, Bhagat Singh recorded under the heading “Religion – the Proponent of the Established Order: Slavery” that “in the Old and New Testaments of the Bible, slavery is endorsed, and God's power does not condemn it.” While trying to understand the causes behind the emergence of religion and its functioning, he turned to Karl Marx.

In his writing titled Attempts at the Synthesis of Hegel’s Philosophy of Justice, under the heading “Marx’s Thoughts on Religion,” he writes: “Man creates religion; religion does not create man. To be human means to be part of the human world, the state, and society. The state and society together give rise to a distorted worldview of religion…”

His approach appears to be that of a social reformist, aimed at overthrowing capitalism and establishing classical socialism. In his notebook, he has included several quotations from the Communist Party’s manifesto.

He also recorded the lines of the anthem The Internationale. In Friedrich Engels’ work, through quotations concerning revolution and counter-revolution in Germany, he is seen opposing his comrades’ superficial revolutionary ideas.

In the country, a series of mob lynchings—executions carried out by crowds—in the name of religion, caste, and the cow have begun, and the references he raised from T. Paine’s Rights of Man remain relevant even today. In his notebook, it is written: “They learn these things from the very governments under which they live. In return, they impose upon others the very punishment to which they have become accustomed… The impact of the brutal scenes displayed before the masses is such that it either dulls their sensitivity or incites a desire for revenge. Instead of reason, they construct their own image based on these base and false notions of ruling over people through terror.”

Regarding “natural and civil rights,” he noted, “It is man’s natural rights alone that form the basis of all civil rights.” He also recorded the words of the Japanese Buddhist monk Koko Hoshi: “It is only appropriate for a ruler that no person should be tormented by cold or hunger. When a person does not even have the basic means to live, he cannot uphold moral standards.”

He provided references from various authors on subjects such as the aim of socialism (revolution), the aim of world revolution, social unity, and many other issues. Bhagat Singh’s associates have noted that while in prison, he wrote four books. Their titles are: 1.Autobiography, 2.Revolutionary 3.Movements in India, 4.The Ideals of Socialism, 5.At the Doorstep of Death. These books were destroyed after he was released from prison, out of fear of reprisals from the British authorities.

Bhagat Singh’s outlook was directed toward building a just, socialist India—free from casteism, communalism, and inequality—in the post-independence era. His writings and articles clearly indicate this vision, and the prison notebook stands as evidence of his profound study.

Bhagat Singh’s prison notebook, is not only a record of his revolutionary thoughts and intellectual pursuits but also a testament to his enduring legacy in the struggle for freedom.

The notebook reveals his meticulous reflections on various subjects—from natural and civil rights to the inherent inequalities of his time. It also highlights his profound analysis of social, political, and religious issues, emphasizing his vision for a just and egalitarian society.

March 19, 2025:

-

-

Kalpana Pandey, Writer

kalapana281083@gmail.com

Phone No. : 9082574315

Disclaimer : The opinions expressed within this article are the personal opinions of the writer/author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of Babushahi.com or Tirchhi Nazar Media. Babushahi.com or Tirchhi Nazar Media does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.